His cousin Freddie brought him on the heist one hot night in early

June. Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days—uptown,

downtown, zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming. First

up was Radio Row, to unload the final three consoles, two RCAs and a

Magnavox, and pick up the TV he left."

His cousin Freddie brought him on the heist one hot night in early

June. Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days—uptown,

downtown, zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming. First

up was Radio Row, to unload the final three consoles, two RCAs and a

Magnavox, and pick up the TV he left."

|

|

| Amazon |

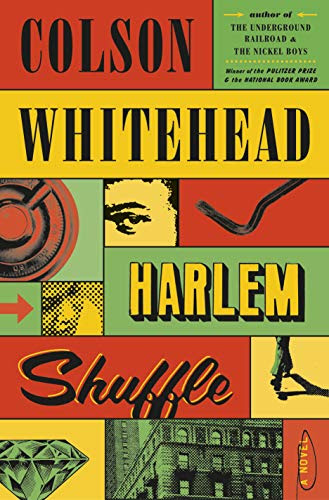

It's a heist novel. It's a character study of a man halfway between legitimate businessman and small-time crook. It's a study of a society that makes it hard to tell the difference.

Grade: B+

This is the third Colson Whitehead novel I've read. The first two ("The Underground Railroad" and "The Nickel Boys") both won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. His latest probably won't be his third consecutive award, but that's only because his subject matter is less weighty.

"Harlem Shuffle" has the structure of a 1950s/1960s crime story, like an old black-and-white gangster movie. It's set in slightly seedy Harlem and features characters like Miami Joe and Tommy Lips. The main character, Ray Carney, is a man who convinces himself he's a legitimate businessman. His side hustle of fencing radios and televisions is just a part of business in Harlem. "There was a natural flow of goods in and out and through people’s lives, from here to there, a churn of property, and Ray Carney facilitated that churn. As a middleman. Legit."

"Harlem Shuffle" is not just a crime story. It's a family saga. Ray was shaped by his father, a small-time crook. Ray's cousin Freddy has a penchant for dragging Ray into his schemes, including the big heist at the center of the plot that threatens Ray's business, his family, even the lives of Freddie and himself. The setting is Harlem. All the main characters are African-American. But change them to Italian-Americans and you could be forgiven for thinking of "The Godfather." Ray Carney may be the main human character in the novel, but Harlem itself dominates every page. Colson Whitehead brings the city to life for readers who have never been on a Harlem street.

"This tour with Munson on his rounds took Carney to places he saw every day, establishments on his doorstep, places he’d walked by ever since he was a kid, and exposed them as fronts. The doorways were entrances into different cities—no, different entrances into one vast, secret city."

No comments:

Post a Comment